Background: I

visited Warrenton, N.C., where my ancestral cousin, Lyndon M. Welborn, trained

for the Confederate army, to learn more about my family’s Civil War experience.

In Warrenton and in later research, I uncovered information about why men

fought for the Confederacy. Personal reasons varied, but slavery kept surfacing

as a main cause.

From my

book-in-progress, Dear Father I Am Sorry To Tell You (Copyright

B.J. Welborn; all rights reserved.):

|

Richard Furman,

1755-1825,

was a prominent minister and president

of America's first Baptist convention.

Furman University in Greenville, S.C.,

took its name from him. |

When

South Carolina broke from the Union, delegates to the Secession Convention in

Charleston attached a “Declaration of the Immediate

Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the

Federal Union” to its 1860 Ordinance of Secession. Three other states

also attached a list of reasons for secession to their ordinances: Georgia,

Mississippi and Texas.

South

Carolina’s declaration stated that a reason to dissolve its compact with the

Union was because non-slave holding states were violating a national agreement

(the retooled Fugitive Slave Act of 1850) to return runaway slaves. South Carolina secessionists

alleged northern states were violating the Fourth Amendment to the

Constitution. The Fourth Amendment stated “No person held to service or labor in one State, under the

laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in consequence of any law or

regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be

delivered up, on claim of the party to whom such service or labor may be

due."

South

Carolina secessionists declared Northern states were “discharging from service”

fugitive slaves; Northerners harbored runaways and helped them flee to freedom.

South Carolina’s secession leaders, mostly members of the slave-owning planter

class, pointed out that South Carolina slave owners had been paying taxes on

their slave property, as required by the Union. Moreover,

South Carolina was exercising a Constitutional right by seceding. South Carolina was a good

Constitutional citizen.

Leading

South Carolinians equated Lincoln with abolitionism. They declared abolitionism a terrifying threat to

Southerners. Historian Walter

Edgar, citing historic newspaper reports in his book South Carolina, A History, writes of the Reverend Richard Furman of Greenville, S.C. Reverend Furman told

his congregation that Lincoln’s first election would mean “every negro in South

Carolina and every other Southern State will be his own master; nay, more than

that, will be the equal of every one of you.” Furman warned that abolitionist preachers would be willing

to marry “your daughters to black husbands.”

|

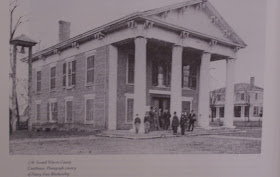

| Warren County's second courthouse was standing when North Carolina troops gathered there for a festive send-off in 1861. The first structure burned down; this courthouse was built in the 1850s. |

North

Carolina did not elaborate its terse Ordinance of Secession.

North

Carolina’s African-American population today totals twenty-two percent, many

still living in the east, where flat sandy land had allowed profitable

plantations, in contrast to the state’s mountainous west. South Carolina today is more than

thirty percent black. The black

population lives mainly in the eastern “Lowcountry,” where huge plantations once

thrived. North Carolina’s black

population currently clusters in Warren County, now forty percent

African-American, and in five surrounding counties with populations more than

fifty percent black.

“I

guess many people living here now are descendants of the slaves who worked the

big plantations around here?” I asked Hunter as we walked to the library. Richard E. Hunter, Jr, Warren County's superior court clerk, reigned as keeper of Warrenton's historical flame.

“That’s

right,” he said. “The sandy soil around here made perfect growing conditions

for tobacco. And cotton.”

Hunter

was right about the library’s riches.

In a basement room dominated by a fine old conference table, I found

shelves of musty books on North Carolina history. I mined nuggets of

information about Lyndon and his regiment, as well as Lyndon’s three brothers

who fought in the Civil War. I

also found a long list of other ancestors who had fought, some who gave the

last full measure for The Cause.

Millions

of American families claim ancestors who fought in the Civil War, which took more

American lives than all other wars in our nation’s history combined, ten percent of the

nation’s population at the time.

Nearly 40 percent of Southerners claim ancestors who fought for the

Confederacy.

The

books in the basement didn’t reveal reasons my forebears became Confederate

fighters, but I am sure that when war erupted, ordinary men who were not

abolitionists joined Federal ranks to preserve the Union, and regular men

indifferent to slavery joined Confederate ranks, aiming to safeguard their way

of life.

Later,

I would learn that Lyndon volunteered for the Confederate army, against his

father’s wishes, because of a matter of the heart. (See Archives, March 15) His brothers fought because the

Confederacy drafted them. One brother, David, petitioned to avoid military

service, but that action ended in devastating defeat.

Coming soon:

The Story of David. See PREVIEWS

page.